August 8th, 2007 by alephnaught

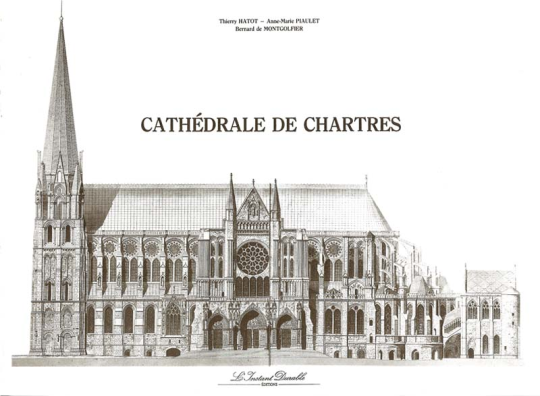

Brochure from Chartres Cathedral paper model – Cathédrale De Chartre

(The following text and pictures are from the paper model kit (you can see the kit as it was assembled at my blog here) I assembled of Chartres Cathedral)

Chartres is more than just a place: first and foremost it is the cathedral. If the name of Chartres echoes so strongly in the heart and mind it is because of this cathedral impressed on the landscape. The lofty spires of Gothic architecture like to tower above all they survey: they need the wide expanse of a plain. Those of Chartres soar up from the « ocean of wheat )1 celebrated by the poet Charles Peguy, and their only backdrop is the sky. The plain of Beauce, ruffled by the winds, seems to have been created expressly to draw man’s gaze towards this embodiment of the spirit. The cathedral also dominates an old town but at the same time is at one with it. In Chartres, one is aware of the extent to which the French cathedral – unlike the cathedrals of England, which have retained certain aspects of the closed world of their monastic origins – has its place in the heart of the city.

Chartres is more than just a place: first and foremost it is the cathedral. If the name of Chartres echoes so strongly in the heart and mind it is because of this cathedral impressed on the landscape. The lofty spires of Gothic architecture like to tower above all they survey: they need the wide expanse of a plain. Those of Chartres soar up from the « ocean of wheat )1 celebrated by the poet Charles Peguy, and their only backdrop is the sky. The plain of Beauce, ruffled by the winds, seems to have been created expressly to draw man’s gaze towards this embodiment of the spirit. The cathedral also dominates an old town but at the same time is at one with it. In Chartres, one is aware of the extent to which the French cathedral – unlike the cathedrals of England, which have retained certain aspects of the closed world of their monastic origins – has its place in the heart of the city.

The cathedral of Chartres was the work of centuries, as is immediately evident from the contrasting styles of the two spires, perhaps the most striking feature of the building and certainly the one that remains the most clearly imprinted on the memory. The present church was finished by the mid-13th century, and while it opened the way for High Gothic there is surviving evidence of the Romanesque style in the Royal portal and the clacher Vieux, the south spire. The Flamboyant style, the Renaissance and eyen the Baroque have also left their mark on Chartres but in a manner that is not discordant. The impression of harmony created is due in great part to the building stone used, a limestone quarried in nearby Bercheres, a little rough in appearance but extremely hardwearing. A more delicate stone was used in the sculptures. The cathedral of Notre-Dame achieves a balance beh\’een qualities or characteristics that are often conflicting: unity and diversity, strength and lightness, grandeur. and a concern for detail, cohesion and development, masterly skill and slight irregularities to dispel monotony and coldness of feeling.

At Chartres, the architecture is inseparable from the magnificent figure sculptures and the stained glass, both seen by the church as part of its teaching programme, pointing the way to revelation. The figurative representation is an open book that rewards close attention for nothing is there by chance. In this respect Chartres is unrivalled in France and perhaps even in Europe. Outside, the sculpture of the three series of triple portals is the legacy of two periods: the Royal portal is the magnificent culmination of Romanesque design, while the two fa~ades of the transept express the youthful vigour of Gothic. Stained glass dominates the interior, and again two periods are represented. If deciphering the complex imagery of the windows appears too arduous a task, admiring their splendid colours is an effortless pleasure. They bathe the cathedral in a soft mystic light conducive to meditation. Steeped in faith, a place of prayer, the cathedral of Notre. Dame is a mirror to the invisible, and for this reason countless generations of pilgrims have hastened their steps to Chartres, to worship and to pray.

The fourth consecutive cathedral in 1134

The cult of the Virgin Mary has long flourished in Chartres and the present cathedral was the fourth church in succession to be built on the site. Tradition has it that a figure of a « Virgin about to bring forth a child )) was worshipped by the druids of the Carnutes in a grotto at Chartres. The image was taken over by early evangelists and transformed into that of the Virgin Mary. The church that was destroyed in 743 dated back to the fourth century and its replacement was burnt down by the Normans in 858. Bishop Gislebert then built a third cathedral of which there remains, under. ground, the semicircular martyrium called the Saint~Lubin chapel, on which rested the apse. In 1020 the building was once again destroyed by fire. Work was immediately begun by Bishop Fulbert on the building of a much larger church almost as long as the present cathedral, but without vaulting in the main nave. The west face of this building was composed of a single tower forming a porch, of a kind that can still be seen at Saint-Benoit.sur-loire. Fulbert built the present crypt, which expands around the Carolingian martyrium.

The last vestages of the Romanesque style

The two towers facade adn the south spire(le clocher Vieux).

Damaged by fire in 1134, Fulbert’s church was given a new facade with two lateral towers inspired by the H form of Norman Romanesque architecture, examples of which can be seen at Caen, in the facades of the Abbaye-aux-Hommes and the Abbaye-aux-Dames. The north tower was begun first but not completed till the beginning of the 16th century. Then came the south tower, better known as the clocher Vieux, which was completed in about 1160. Like the other tower it is square up to the present level of the Gallery of Kings but higher up has an octogonal spire («faultless and unfailing» in the words of Peguy), a stone pyramid rising boldly towards the sky. The connection between tower and spire was superbly achieved by adding high gabled dormers on the faces of the spire, alternating with four small corner pinnacles. The triple portal called the «Royal portal», surmounted by three windows, was installed between the two towers in about 1150.

The sculptures of the Rogal portal between the towers.

Whether one considers it as the culmination of Romanesque art or as the dawn of Gothic, the western portal is the sculptural masterpiece of the second half of the 12th century. The overall theme is the glory of God as revealed in the advent and the final triumph of Christ. On the sides of the three doors stand nineteen statues of characters from the Old Testament called columnar figures because they form a whole with the column they back onto, echoing their vertical rhythms. While of monumental grandeur, the statues are finely carved with distinctive facial expressions and drapery in long delicate folds. The theme of the three tympanums of the Royal portal is the incarnation and glorification of the Word. On the central tympanum is the Christ in Majesty as represented in the Apocalypse between four figures symbolising the Evangelists.

The inspiration is theological, the tone solemn with little room for narrative, all features that root the Royal portal in the Romanesque tradition. However the narratIve mode is apparent in the small-scale compositions: the capitals atop the columnar figures with scenes from the life of Christ, or the archivolts of the left door depicting the work of the seasons and the signs of the zodiac. On the archivolts of the right door are sculpted the symbols of the seven liberal arts, embodying the sum of humanknowledge. Already we are very close to the encyclopaedic spirit that will find expression in the monumental sculptuure of the 13th century.

The sky blue of the stained glass windows surmonting the Rogal portal.

The three windows above the Royal portal contain magnificent stained glass that lends its glow to the interior of the facade. It is the prelude to the symphony of colour that fills the cathedral with radiant light. The master glass-artists of the 13th century, despite all the wealth of their skill, never quite equalled the ethereal limpidity and brilliance achieved by these artisans of Chartres. The predominant colour, especially in the Tree of Jesse design in the west window, is a magnificent sky blue. The same style of this Chartres atelier can be found in the stained glass windows of the cathedrals of Le Mans, Angers and Poitlers.

The dawn of Gothic art

The rebuilding of the nave transept and choir after the fire of 1194.

On June 10, 1194 a fire destroyed Fulbert’s basilica, leaving the two towers and the clocher Vieux, the Royal portal and the three windows above it. The main relic of the cathedral, a veil of the Virgin, was also spared and this was hailed as a miracle by the people of Chartres and immediately spurred them on to rebuild their church. There was a great upsurge of collective fervour and very few cathedrals have been completed in so short a time. Work was begun the year of the fire and progressed so swiftly that most of the new building was already standing by about 1220. The nave must have been finished before the choir, which in turn was completed before the upper parts of the transept. The cathedral was consecrated in 1260, in the presence of King Saint Louis.

The resulting effect is one of overall unity, enhanced by the fact that the clear grandiose plan of the building was the work of a single unknown master. The structure of the cathedral places it at a turning point in the development of medieval architecture. Although diagonal rib vaulting was used in the first great Gothic churches, such as those of Noyon, Laon, Saint-Remi de Reims and Notre-Dame de Paris, the conception of the interior space and of the equilibrium of forces was still Romanesque in spirit. The large square vaults of the main nave were sexpartite, so called because they were divided by their ribs into six interdependent parts. Their thrust was balanced by the gallery vaults surmounting the aisles. The interior elevation of the main nave presented a series of four horizontal planes: the rows of arcades bordering the aisles, the bays of the galleries, the triforium – a narrow decorative arcade – and the upper windows. As a result the interiors were dimly lit and there was a lack of vertical push.

It was at Chartres that the way was opened for High Gothic architecture. Its example was later taken over, notably in Reims and Amiens. The first innovation was in replacing the square sexpartite vaults by rectangular vaults with diagonal ribs. Their thrust was no longer buttressed by galleries but by arches thrown outwards, transmitting the force towards the piers: these were the flying buttresses that henceforth became an essential feature of Gothic architecture. The main nave thus became a three-story elevation: the arcades bordering the aisles, the triforium and the clerestory windows. This omission of the galleries heightened the aisles, and hence the arcades alongside them, lengthened the upper windows and increased the vertical emphasis in the nave. Thus simplified the entire stucture of the building becomes a play of forces expressed by the intersecting ribs, their supports (clusters of columns) and, outside, the flying buttresses.

The system thus conceived strengthened the role of the ribbing and: reduced that of the traditional wall, which became hardly more than infilling. The heightened windows were able to occupy all the available surface in the aisles and the upper story of the main nave. Void prevails over solid and the light, although softened by the rich colours of the stained glass, is able to stream in. In among the innovative features of Chartres there remain many traces of the past, and strength is still in greater evidence than grace. The flying buttresses of the nave appear squat and powerful and it is only later in the chevet that a greater impression of lightness will be achieved.

However, the distinctive personality of the church is expressed in many other ways. The cathedrals of the 12th century, of the kind at Noyon and Laon for example, with their four-story elevations put the emphasis on horizontality and length (as in most English cathedrals). At Reims, Amiens and in particular at Beauvais, the balance is in favour of the vertical. At Chartres the interior has an admirable equilibrium; the main nave is not only very high but is also unusuaHy wide. The aisles are nearly as high as the upper windows. This harmony also resides in the fact that the choir with its apse is almost the same length as the nave. The transept is exceptionally large. The aisles have retained the purity of their design and their luminosity because, with one exception, they were not doubled afterwards with chapels. The curving bays of the ambulatory have distinctive vaulting. The cathedral was designed to have nine towers, including the two of the west facade, already completed in the middle of the 12th century. Each facade of the transept was to be flanked by two towers and two other towers were planned to rise up on either side of the choir. These six towers were begun but built only up to the base of the roof. As for the ninth, which would have surmounted the crossing of the transept, it never existed. This is perhaps as well. Had the towers been completed their bristling array would have detracted from the upsweep of the famous spires of the west facade.

A vast programme of sculpture in the transept portals.

The building of the present cathedral begun in 1194 included a vast programme of monumental sculpture. Tbe Royal portal was’of-course still standing intact in the west front after the fire and so the unusual decision was taken of carrying out this programme on either side of the transept, in the north and south porches. The facades of the transept, like the transept itself, were exceptionally large and were able to accommodate a triple portal, this bringing the total to three with the Royal portal, which was integrated afterwards into the grand design, conceived in about 1200. The north triple portal, which dates essentially from the beginning of the 13th century, has for its general theme the Incarnation as announced by the Old Testament and accomplished through the Virgin Mary, Mother of God. There was a clear development in the style of the large statues in the embrasures and window piers in comparison with those of the Royal portal Although still backing onto the columns the figures stand out by their bold relief and lively attitude. There is greater variety and individuality in their expression but they all possess the sober nobility appropriate to the role they have to play, that of announcing and preparing the coming of the Redeemer. The figure of Saint John the Baptist is particularly expressive. In the tympanum of the right bay there are scenes from the Old Testament and in that of the left bay episodes from the childhood of Christ. The tympanum of the central bay shows the Assumption of the Virgin. The archivolts of the three portals and of the porches, executed a little later and which jut out from them, are filled with small finely carved figures whose iconography is of great interest. The theme of the south triple portal, completed a little later, is the Church of Christ and the purpose of mankind. In the window pier of the central bay there is an admirable figure of Christ teaching and blessing while on either side stand the statues of the twelve apostles, of an austere dignity. The statues of the martyrs and those of the Confessors in the embrasures of the left and right bays respectively are more distinctive. The lateral tympanums illustrate the martyrdom of Saint Stephen and episodes from the lives of the saints. In the tympanum of the central bay there is an imposing sculpture of the Last Judgement. As in the north portal, the three porches were executed at a slightly later date. The statues, especially those of Saint George and Saint Theodore, are in a more delicate, fluid style, as are the statuettes and bas-reliefs, which might have been designed as illustrations for a kind of Christian encyclopaedia.

The maze.

One can still see engraved on the stone floor of the nave the large medieval maze whose path pilgrims would follow on their knees as a penance. During pilgrimages large numbers of the faithful would sleep overnight in the cathedral, which served as a kind of huge hostel.

Flowering of the glass-painters’ art.

The lengthening of the windows in the design of the church in 1194 provided an enormous area for the art of the master glass-painters. Like the sculptures, the stained-glass windows were executed, if not at the same time as, only a little after, the main construction work, so that by the middle of the 13th century the cathedral had virtually all the splendid decoration as we know it today. Compared with the windows above the Royal portal, the later examples have colours that are deeper and more intense but perhaps less luminous. It is difficult to find one’s bearings in the stained glass windows of Chartres, which do not have the same strict distribution of figures as in the sculptures of the portals. Most of the clerestory windows represent tall figures designed to be seen from a distance. Particularly impressive are the two vast compositions of the transept facades, each with a rose surmounting five windows. In contrast, the windows of the aisles and the ambulatory depict numerous scenes with small figures whose rich iconography is difficult to summarize in a few words. In addition to the beauty of their colours and the delicacy of the drawing, the windows contain a great variety of medallions, of different shapes and arrangements.

The lightness of the Rayonnant style

Over the centuries additions were made to the building. In the second half of the 13th century, the sacristy (not shown on the model) was built on to the north side of the chancel and shows the evolution of Gothic architecture towards the lightness of the Rayonnant style. In 1326 an elegant two-tier construction was added to the chevet whose upper storey houses the Saint Piat chapel (not shown on the model), joined to the cathedral by a staircase that forms a picturesque covered bridge, decorated with fine stained-glass windows of the same period.

The triumph of the Flamboyant Style and the Renaissance

The triumph of the Flamboyant Style and the Renaissance

In 1417, between two buttresses on the south flank of the nave, was added the Vendome chapel, a splendid example of the early period of the Flamboyant style. Its large windows contain stained glass typical of the 15th century by their light, bold colours. Again, the windows at Chartres were executed just after building was completed. The main additions to the original structure were made during the first half of the 16th century, which saw the culmination of the Flamboyant style and the arrival from Italy of Renaissance themes. The principal architect of these changes was Jean Tixier, called Jean de Beauce. Between 1507 and 1513 he completed the north tower by building the famous clocher Neui, a little higher than the clocher Vieux but different from it, in particular by its exuberant decoration, tempered nevertheless by a great lightness.

To ensure that services could be carried out in an atmosphere of calm the canons of the cathedral

chapter asked the same master to isolate the choir from the aisles and ambulatory, often thronged with the faithful, by a sculpted stone parclose. The screen was begun in 1514. This magnificent decorative work, which can be seen from outside the choir, comprises a sort of openwork canopy in its upper part, a showpiece for the elaborate Flamboyant style, a substructure with medallions inspired by the Renaissance style and between the two a series of forty niches containing sculpted compositions by various artists depicting the lives of Christ and the Virgin.

The first of these groups still retain the imprint of the Gothic, but subsequent figures sculpted towards the middle of the 16th century are in the Renaissance style, while the influence of Baroque can be seen in the compositions of the 17th century and beyond to 1714 when the screen was finally completed. From one end to the other the parclose is a series of tableaux vivants that unfold like the scenes of a medieval Mystery Play.

The last transformations

In the second half of the 18th century the canons decided to update the style of the choir and bring it into line with the classical taste of the day. To them we owe the present high altar which is largely dominated by the huge marble group sculpted by Charles-Antoine Bridan depicting the Assumption, whose swelling forms are still close to the Baroque style. In 1836, a fire due to the carelesseness of a plumber completely destroyed the upper woodwork or « forest » supporting the roof. It was replaced by a metal framework, ,which was remarkable for the period. The roof was redone in copper sheets, which with time have taken on a grey-green hue and blended with the stone to become inseparable from the landscape of Chartres and an integral part of this, the most stirring of cathedrals.

Bernard de MONTGOLFIER

lnspecteur general des Musees de la Ville de Paris

Revisions:

There are no revisions for this post.

6:39 am on December 10th, 2011

[…] have been nice. I bought a paper model of the cathedral, which I put together over a month – here is a link to the English language brochure that came with the model, and here’s a link to my blog to […]

Translate