The

exhibits were fun and interesting, including a special exhibit on the wandering

Jew in art. The quarter was pretty lively and open, even though it was Christmas.

The

exhibits were fun and interesting, including a special exhibit on the wandering

Jew in art. The quarter was pretty lively and open, even though it was Christmas.

|

|

Ticket

for entry to the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme:

a Contrat de Mariage (catuba) from Modène, Italy

|

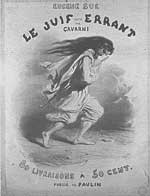

Their special exhibit was on "The Wandering Jew" - here is the main part of the pamphlet on the exhibit:

The legend of the Wandering Jew took shape in Benedictine monasteries in England in the 13 Ih century, where chroniclers and illuminators sought to enrich the corpus of anecdotes concerning the life of Christ. Drawing on oral tradition and a variety of writings, they described a figure who witnessed the Passion and, having offended Christ, was condemned to restlessness until the end of time. The first stories attesting to this legend, Roger de We ndover's Flores Historianum chronicles (1 228) and Matthew Paris's Chronica majora @l 235) were copied throughout Europe. Although the most ancient visual depictions of the Wandering Jew date back to the 1 2 Ih century, the most explicit images, those of the Wandering Jew's meeting with Christ, figure in Matthew Paris's manuscript and in the psalter illuminated by William de Brailes in 1 240. There are also representations of the Bearing of the Cross and the Crucifixion in which a figure holding a walking staff can be interpreted as a Wandering Jew, for instance in Martin Schongauer's engraving Christ Carrying the Cross (1 475-80).

From the 13th to the 17th century, the legend evolved. The Wandering

Jew, now called Ahasver, "eternally" walked the roads of Europe.

The development of chapbooks helped the story's dissemination. A popular chapbook

entitled Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzehlung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus,

published in Germany in 1 602, was immediately translated all over Europe.

The tale was published in France

· under the title Courte Description et Histoire d'un Juif nomm6 Ahasv6rus

(1605) and taken up again in the form of a lament with numerous variations,

the most famous being the Complainte brabangonne (circa 1800), in which the

Wandering Jew was renamed Isaac Laquedem. It was the fantastic aspect of the

character and story which then dominated: passing through the great towns,

Ahasver told his tale, in which he gave his account of Christ's Passion, to

call for the defence of religion and repentance. He also gave his account

of the history of the world, spoke every language and predicted the future.

He bore witness to the inexorable passing of time, was frightening sometimes,

but above all fascinated and aroused sympathy.

In the 1 gth century, technical advances transformed printing

from craft to industry and print runs of engravings attained astronomical

numbers. Popular prints, inspired by the scholarly print and frequently republished,

were hawked in the towns but above all in the country. In France, the image

of the Wandering Jew, usually framed by the text of the Complainte brabangonne,

spread throughout the land. In the

3 early 1 glh century, the Pellerin works at Epinal dominated the popular

print market.

There was a marked evolution in the image, both in its composition and in the message it conveyed. In the second half of the 1 9" century, portraits of the Wandering Jew, both commonplace and radicalised, gave an increasingly negative and discriminatory vision of the wonderful walker. Some were even marked by virulent Antisemitism. Advertising made its own use of the figure, turning him into a symbol of the virtues of longevity and endurance.

Romanticism imposed a culturally, politically and so-cially

significant itinerary on the figure of the Wandering Jew. The legend first

entered the domain of romantic literature in Germany, in the poems of Goethe

and Schubart, who inspired in particular the painters Kaulb'ach and Caspar

David Friedrich. Although this did not emancipate him from the Christian vision

of the legend,

Ahasver's fate rendered him worthy of the Romantic pantheon, 4 6 who regarded

him as a solitary, tragic hero, plunged into terrible, pathetic solitude.

In France, the influence of German Romanticism was felt by poets and writers

such as Bbranger and Edgar Quinet and, following them, by artists such as

Ary Scheffer and Marie d'Orl&ans. Yet it was above all Eugene Sue's novel

Le Juif errant (1844-1845), which renewed and popularised this figure, turning

him into a champion of the fight for social justice. The Wandering Jew became

a metaphor of the people and his story a vehicle for contemporary ideological

movements such as Antijesuitism and Utopian socialism. Later, partisans of

republican secularism transformed Eugene Sue's Wandering Jew into a symbol

of humanity's onward march and social progress.

In the second half of the 1 9" century, artists began to take an interest in the legendary figure of the Wandering Jew, interpreting him in diverse ways. Some, such as Courbet, identified with him, conceiving the artist's role in society on the one hand as passer-by, observer and witness and on the other as a man committed to the causes of his time. Like B6ranger and Eug6ne Sue, they saw the Wandering Jew as an allegory for the fight for justice, freedom I 0 and solidarity.

The Wandering Jew's notoriety was also manifest in the theatre (Caigniez, Merville and Mallian, Sue) and on the operatic stage (Fromental Hal6vy composed a popular opera with a libretto by Eugene Scribe).

Gustave Dore, moved by Bdranger's song of the Wandering Jew - for which his brother Ernest Dor6 composed a music - and by the poem by Pierre Dupont, executed twelve engravings which made a profound and enduring mark on the aesthetics and perception of the figure. Among other artists interested in the Wandering Jew were Gustave Moreau and his pupils Adrien Gilles and Georges Rouault.

The subject of the Wandering Jew also interested less wellmeaning individuals of learning and artists steeped in an Antisemitism often rooted in militant Catholicism. The criminalization of the phenomenon of the wanderer was associated with the racism emerging in pseudo-scientific formulations, notably in the world of psychiatry. Henry Meige, following his teacher, Charcot, elaborated on the case of those he called "wandering neuropaths", whom he saw as descendents of Cartophilus, the Wandering Jew. From then on, the Jews were considered asocial pariahs of pathological instability, incapable of putting down roots in their host society.

Late 1 gth century Antisemitism violently threw into question the Jews' presence in society and their status as citizens. It used and combined several negative images of the Jew, including the Wandering Jew. But in antisemitic figurative rhetoric, particularly that of the antidreyfusards, references to the Wandering Jew are made only indirectly, through allusions (the stick or umbrella, or the business purse or wallet).

In the second half of the 1 glh century, Jewish thinkers and

artists became conscious of the significance of the figure of the Wandering

Jew that had been fashioned by Western Christian imagination. Ahasver's identification

with the tragic fate of the Jewish population, above all in Eastern Europe,

gave rise to creations which were simultaneously the result of the artist's

inner questioning and visions of persecution.

12 Emergent Zionism sought to put an end to Ahasver's fate, promising him

an end to exile and redemption. But the Shoah rekindled Jewish artists' questioning

of their nation's destiny, resurrecting in the image of the Wandering Jew

the spectre of wandering as a fatal phenomenon.

Complementing the exhibition, a series of written, graphic and musical documents are on exhibit in the Media Library.

Send

email to Bob at electricbob@alephnaught.com

Send

email to Aviva at avivakramer@earthlink.net